On the surface, SlopAds appeared as yet another run-of-the-mill cluster of Android apps—AI-themed tools, simple utilities, mild entertainment, etc. But under the hood, there was something far more insidious: a sophisticated ad-fraud campaign that generated 2.3 billion ad bid requests per day, using 224 apps with over 38 million downloads globally. This operation used clever obfuscation, steganography, attribution abuse, and hidden WebViews to monetize over ad inventory fraudulently.

This article describes how SlopAds worked, how it was discovered, what its implications are, and what lessons it holds for users, ad networks, platforms, and regulators.

What is SlopAds?

“SlopAds” is the name given to a large Ad-fraud / Click-fraud operation uncovered recently by HUMAN’s Satori Threat Intelligence & Research Team, in collaboration with Google.

Key statistics:

-

More than 38 million downloads across Google Play, spread over 228 countries and territories.

-

At peak, the network was generating ~2.3 billion ad bid requests per day.

-

Main sources of traffic: about 30% from the United States, 10% from India, 7% from Brazil.

So what was really going on? How did 224 apps, many seemingly innocuous, generate such massive ad-fraud?

How SlopAds Operated: The Fraud Mechanisms

SlopAds was not a crude, easily detected fraud scheme. It used multiple layers and techniques to hide its activity. The operation had several components:

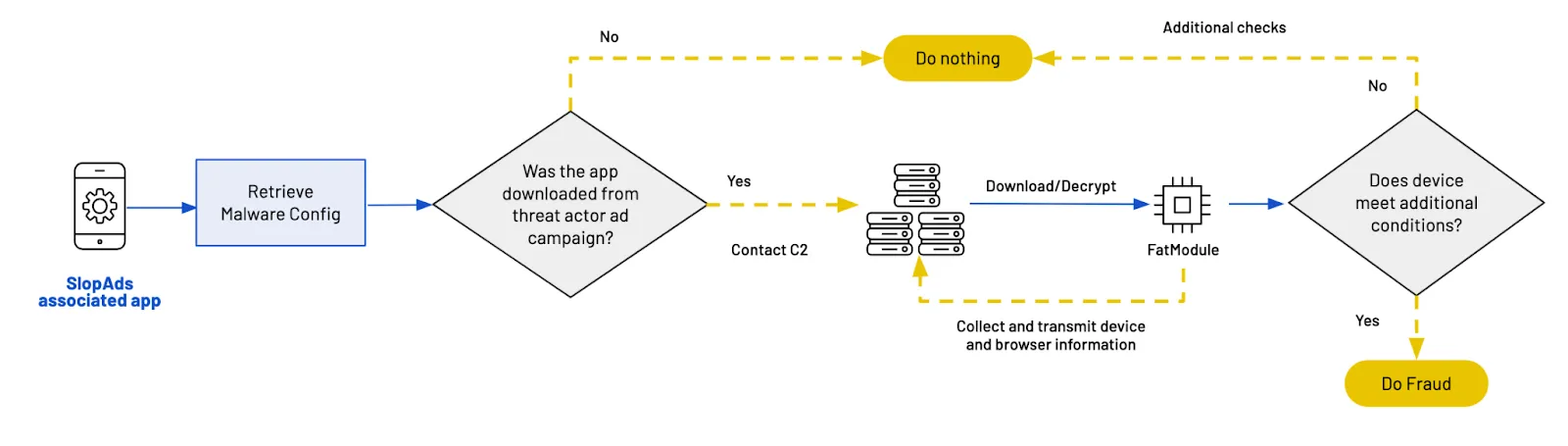

1. Conditional Fraud Based on Attribution

One of SlopAds’ key tactics was to check how the app was installed. Specifically, it used mobile marketing attribution SDKs to see whether the install was “non-organic”—i.e., whether the user clicked on an ad (run by the threat actors themselves) and from that ad was redirected to Google Play to download the app. If so, the app would be flagged for fraud behavior; otherwise, for organic installs, it behaved like a benign, regular app.

Why is this significant?

-

It reduces risk of detection, because apps looked clean in many ordinary use-cases.

-

Organic installs (which are more visible to security researchers, some analytics, etc.) weren’t used in the fraud behavior.

-

This conditional behavior meant that only certain traffic (the ones that came from threat actor-driven ad campaigns) triggered the malicious code.

2. Payload Delivery via Steganography

Another high-sophistication tactic: the fraud payload (named FatModule) was delivered via image files (PNG), using steganography. The threat actors split the payload into multiple PNG images, which appear innocent. Once downloaded on the device, these are decrypted and reassembled into the malicious APK or module.

This has several advantages:

-

Avoids detection via signature-based malware scanners, because image files are generally considered benign.

-

Camouflages the real malicious code inside a medium that is unlikely to trigger heuristics.

-

Makes reverse engineering more complex.

3. Hidden WebViews & Domain Chains

Once the payload was active, SlopAds apps created hidden WebViews—essentially invisible browser windows running in the background. These WebViews would:

-

Fetch device and browser information.

-

Navigate to threat actor-controlled “cashout” domains (often HTML5 games or news sites), where ads were served.

-

Simulate ad impressions and clicks to generate ad revenue fraudulently.

In addition, the chain of redirection often passed through multiple domains to sanitize referrer data and tracking metadata, making fraudulent bid requests look more legitimate.

4. Obfuscation & Anti-Detection Tactics

SlopAds deployed a laundry list of ways to avoid detection:

-

Checks for debuggers, emulators, or rooted devices. If any of these are present, the fraud module is often not activated.

-

String encryption and packed native code (making static analysis harder).

-

Use of marketing attribution signals to avoid fraud being triggered on devices likely to be under scrutiny.

-

Using remote configurations (Firebase Remote Config) to deliver encrypted instructions or parameters.

Discovery & Response

SlopAds was discovered when HUMAN’s Satori Threat Intelligence team identified anomalous patterns in ad bid traffic and installs. Investigation revealed the cluster of apps, the fraud mechanisms, and then they worked with Google to remove the offending apps from the Play Store.

Google’s Play Protect has since been updated to detect similar behaviors. Users of Android devices were also warned to check for and uninstall any of the identified SlopAds apps.

Researchers also reported that even though 224 apps were identified at the time, there were over 300 promotional domains used to drive traffic to these apps. That suggests the operation was large and possibly expanding.

Impacts & Implications

The SlopAds ring is more than just a headline—it points to important risks and takes lessons for multiple stakeholders.

For Advertisers & Ad Networks

-

Massive wasted ad spend: Ad networks may pay for bid requests or impressions generated by fraudulent apps, thinking that real human eyeballs are seeing them.

-

Distortion of analytics: Attribution and conversion metrics get polluted when apps behave differently depending on whether install is organic or driven by an ad.

-

Trust erosion: Fraud undermines confidence in digital advertising, particularly mobile advertising, and raises costs for everyone.

For Platform Owners (Google / App Stores)

-

Challenge of app review: Apps can appear benign at first, and bad behavior is only triggered under certain conditions, making detection during review harder.

-

Need for more sophisticated detection tools: Steganography, remote encrypted payloads, hidden WebViews – these are more advanced than typical ad-fraud methods.

-

Regulatory / legal exposure: Platforms may be held partly responsible for failing to prevent such fraud if detection is lackluster.

For Users

-

Security risk: Users who install such apps may be exposed to malware (the FatModule), privacy breaches, or have their device used as a proxy for fraudulent traffic.

-

Unwitting complicity: Many users may simply download an app, expecting benign function, only to find their device compromised or battery/data usage increasing.

-

Difficulty of detection: Unless the user is tech-savvy or has security tools that warn them, many of these apps may fly under the radar.

For the Ad Fraud Ecosystem & Security Researchers

-

Arms race intensifies: As fraudsters adopt more technical and abstract evasion techniques, ad security must respond with more advanced detection methods.

-

Attribution tools themselves being turned into tools for fraud.

-

Need for cross-industry collaboration: Ad exchanges, networks, platforms, researchers, and regulators must share signals to catch these networks.

Why SlopAds Is Different / More Sophisticated

SlopAds stands out for several reasons over many previous fraud operations:

-

Conditional activation – fraud only when certain conditions are met (non-organic installs) vs. blanket malicious behavior.

-

Steganography for payload delivery – hiding the malicious module inside PNG images to avoid detection.

-

Hidden WebViews and domain redirects – more stealth and masking of traffic.

-

Scale – hundreds of apps, tens of millions of installs, billions of bid requests per day.

-

Rapid scaling and adaptability – promotional infrastructure with many domains; test new apps; remote config to adjust behavior.

This is not an amateur campaign, but one run with technical sophistication, investment, and likely coordination by a well-resourced group.

Lessons Learned & Best Practices

Based on SlopAds and similar fraud rings, what should different stakeholders do?

For Platform Providers (like Google Play)

-

Strengthen review and detection for apps that include attribution SDKs: flag apps that check whether installs are organic vs non-organic, especially if behavior diverges.

-

Inspect image files more rigorously: include steganography detection in security pipelines.

-

Monitor hidden WebViews behavior and unusual domain chains or redirection patterns.

-

Increase transparency and communicate with users when apps are found malicious, including pushing uninstall warnings.

For Ad Networks / DSPs (Demand Side Platforms)

-

Validate traffic sources more carefully: high bid request volumes from apps should be examined, especially from unknown or less-trusted publishers.

-

Use anomaly detection on bid request patterns, referrer sanitization, and rapid redirect chains.

-

Demand transparency from attribution SDKs and partners about whether installs are from campaigns and how attribution is handled.

For Developers & App Publishers

-

Be cautious using third-party SDKs: ensure they are well audited and do not include hidden or unnecessary permissions.

-

Monitor your own app’s traffic, behavior, battery usage, and usability metrics: if users complain or devices heat up, investigate.

-

Avoid embedding suspicious domain or code redirection logic unless needed; document all external dependencies.

For Users & Consumers

-

Install apps from trusted developers; check reviews, permissions, and questionable behavior (battery, data usage).

-

Use device security tools and occasionally check what apps are using data, background services, etc.

-

Uninstall apps that seem to have little legitimate functionality but ask for many permissions.

For Regulators

-

Update regulation around ad fraud to consider modern tactics (e.g. obfuscation, attribution abuse).

-

Ensure ad networks and platforms have obligations to detect, report, and remediate fraud.

-

Possibly require certain transparency or auditability for attribution and ad bidding systems.

What’s Next? Risk & Future Trends

Given what SlopAds has shown, here are likely future developments or risks:

-

More stealth & multi-stage payloads: Using more steganography, split payloads, delayed activation, etc.

-

Attribution abuse becomes more routine: Fraudsters will use signal from attribution tools not only to trigger fraud but to hide in the noise.

-

AI-assisted detection vs AI-assisted fraud: As detection becomes more automated, fraud actors will use AI or generative tools to adapt code to evade those detections.

-

Cross-platform expansion: Similar tactics may move to iOS, or hybrid web-app environments, or even cross-device ad ecosystems.

-

Regulatory crackdown: As damage becomes clearer, stricter laws or enforcement actions may follow.

-

User education becomes more important: People will need to be more critical about app behavior, permissions, and suspicious apps.

The SlopAds campaign stood out not just for its massive scale but for its sheer technical ingenuity. Let’s break down its mechanisms in more detail:

1. The FatModule Payload

At the core of the operation was a module dubbed FatModule. Instead of being shipped directly in the APK file on Google Play, it was cleverly hidden. Once the app was installed under the right conditions (non-organic installs), FatModule was fetched remotely.

-

Payload Assembly: Pieces of the module were stored inside PNG images. Each piece on its own appeared harmless, but once downloaded, they were reassembled like a digital jigsaw puzzle.

-

Dynamic Loading: This module was loaded into memory at runtime, meaning that during static analysis, many security tools would see nothing suspicious in the original APK.

-

Encrypted Communications: Instructions came via Firebase Remote Config, encrypted, so that even network analysis could struggle to determine intent.

This shows the increasing trend of modular malware, where apps look harmless during store vetting but later download or activate malicious code only after installation.

2. Hidden WebViews and Traffic Laundering

Once the payload was active, apps created invisible WebViews that ran silently in the background. These were not ordinary browsing sessions:

-

Headless Mode: The WebView had no visual interface, invisible to users.

-

Multiple Redirect Chains: Requests were passed through layers of domains to strip metadata and obscure origin. Some domains mimicked legitimate ad servers or news/game portals.

-

Click Simulation: Fake clicks and impressions were generated automatically. Since the WebViews had device context, these clicks looked genuine to ad networks.

This tactic of “traffic laundering” is especially damaging because it undermines the integrity of real-time bidding (RTB) systems.

3. Attribution Manipulation

The fraudsters cleverly exploited mobile attribution SDKs, which are commonly used in marketing to track where installs come from. By only activating the fraud module when an install was tagged as “non-organic,” they minimized their detection risk.

Think of it like a burglar who only strikes when no cameras are recording—SlopAds was selective in when to misbehave. This conditionally malicious behavior is part of why it flew under the radar for months.

Comparing SlopAds to Previous Ad Fraud Campaigns

SlopAds didn’t emerge in a vacuum—it belongs to a long lineage of sophisticated ad fraud rings. But it shows clear escalation compared to older campaigns:

-

Joker Malware (2019-2021): Focused on premium SMS fraud and click injections. Much smaller scale compared to SlopAds’ 2.3B daily bid requests.

-

Chamois Campaign (2017): A large Google-identified fraud ring also based on hidden code. But Chamois relied more on fake ad traffic generation, while SlopAds used steganography and attribution tricks.

-

Poseidon (2022): A fraud scheme with complex obfuscation layers uncovered by HUMAN. Poseidon set the stage for SlopAds, but the latter took modular payload delivery to the next level.

Each campaign is more stealthy and technologically advanced than the last. SlopAds’ use of steganography alone marks a turning point, signaling that future ad fraud could borrow even more from cyber-espionage playbooks.

The Global Economic Impact of Ad Fraud

To understand why SlopAds matters beyond cybersecurity circles, consider the economics of ad fraud.

-

Global Losses: Ad fraud is estimated to cost advertisers over $80 billion annually by 2025. ([Juniper Research])

-

Wasted Spend: Every fraudulent impression or click means advertisers are paying for nothing—draining marketing budgets.

-

Inflated Bidding Markets: With 2.3B fake bid requests per day, SlopAds artificially increased competition in ad exchanges, raising costs for legitimate advertisers.

-

Trust Erosion: Brands lose confidence in mobile ads when they see low ROI, which could impact the digital advertising ecosystem itself.

For comparison, SlopAds alone may have accounted for over 1% of all daily programmatic bid requests worldwide. That level of fraud directly distorts the entire marketplace.

Why SlopAds Signals a New Era of Fraud

SlopAds isn’t just another fraud scheme—it points to a shift in strategy:

-

Hybrid Malware + Ad Fraud: The blending of advanced malware techniques (modular payloads, steganography) with traditional ad fraud tactics.

-

Global Reach at Scale: Unlike localized fraud rings, SlopAds spanned 228 countries, proving fraudsters now operate at truly global levels.

-

Attribution Abuse as a Shield: Using legitimate marketing SDKs against advertisers, making detection harder.

-

Continuous Obfuscation Arms Race: The use of encryption, dynamic loading, and conditional triggers suggests future campaigns will be even more adaptive.

This raises questions: If fraudsters can evolve this quickly, can detection systems keep up?

Long-Term Implications for the Industry

For Advertisers

Marketers must demand transparency from their ad partners. Knowing where impressions originate and auditing supply chains will become standard practice. Without that, billions will continue to be wasted.

For Ad Tech Platforms

Expect more emphasis on fraud-resistant RTB protocols, perhaps with blockchain-based verification or zero-knowledge proofs to validate impressions without exposing user data.

For Cybersecurity

SlopAds blurs the line between cybercrime and ad fraud. Techniques once reserved for espionage (steganography, obfuscation, modular payloads) are now mainstream in fraud campaigns. Security researchers must expand their scope accordingly.

For Regulators

Ad fraud may soon be treated not just as “business risk” but as a form of financial crime or even cyber-terrorism, given the global economic losses it creates. That could mean tougher penalties and more legal oversight.

Could AI Help Catch the Next SlopAds?

Ironically, AI may be both the problem and the solution.

-

Fraudsters’ Use of AI: Generative AI can produce endless app variations, rewrite obfuscated code, and even simulate more “human-like” click behavior.

-

Defenders’ Use of AI: Machine learning models trained on network traffic patterns and user behavior could detect anomalies at scale.

The real challenge: ensuring that defenders’ AI evolves faster than fraudsters’ AI.

User Awareness: The Final Frontier

At the end of the day, millions of users downloaded SlopAds-infested apps because they appeared legitimate. User awareness remains one of the weakest links.

Tips for users:

-

Stick to apps from known developers and publishers.

-

Check reviews carefully—especially for sudden updates or generic AI-themed apps with many installs but poor ratings.

-

Monitor your device: If battery drain, overheating, or unexplained data usage occurs, suspect malicious activity.

Conclusion

SlopAds is a wake-up call. A well-engineered, large-scale ad fraud operation, harnessing 224 apps, 38 million downloads, and delivering 2.3 billion ad bid requests daily, all while hiding behind layers of technical obfuscation. It reveals just how vulnerable mobile ad ecosystems can be when fraudsters combine scale, stealth, and innovation.

For advertisers, platforms, and users alike, the message is clear: ad fraud is not just about volume anymore—it’s about the sophistication of tactics. Detection must keep pace, ethics must be enforced, and vigilance must become normal.

SlopAds has been disrupted, but it almost certainly won’t be the last of its kind. Unless the industry responds strongly—with better tools, stricter oversight, collaborative intelligence sharing, and heightened awareness—these rings may easily evolve, multiply, and cause even greater damage.